The Boma

Welcome to ‘The Boma’—a new podcast about livestock in the developing world—the cattle, camels, sheep, goats, pigs and poultry—that provide billions of people with nutrition, income, resources and livelihoods. How can small scale livestock systems be sustainable, as well as profitable? How can they help protect the environment? Do they harm or enhance human health? Check out The Boma to hear diverse perspectives on some of the hottest topics debated today and dive deep into the best and latest scientific research on livestock and development. ****** The Boma is hosted by Global Livestock Advocacy for Development (GLAD), a project of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The Boma

Antimicrobial resistance. A tale of two worlds, or a global threat?

As long as we have had ways to destroy microbes, microbes have been fighting back. Alexander Fleming, who discovered the world's first antibiotic, penicillin, warned that misusing antibiotics could lead to antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

He was right. Today AMR can be found worldwide and is a serious problem. If it is not tackled now, by 2050 one person will die every three seconds because of AMR.

The Boma presenters Brenda Coromina and Elliot Carleton explore how resistance develops, the scale of the problem, and why it can be found in the most surprising places. Today's episode features Arshnee Moodley, the leader of the Antimicrobial Resistance Hub at ILRI. She talks us through what action countries need to take against AMR to avert a grim future, and why each country needs a different plan.

High-income countries can apply resources and large investments against AMR in ways which low-income countries can't. But AMR isn't just a high income problem or a low income problem. With the ease at which it can spread around the Earth, it's everybody's problem.

Elliot: Welcome Back to The Boma. A podcast from the International Livestock Research Institute where we discuss how sustainable livestock is building better lives in the Global South.

My name is Elliot Carleton.

Brenda: And I’m Brenda Coromina.

Elliot: Today, we’re going to carry on the discussion we started in the previous episode about Phages, one approach to tackle antimicrobial resistance, or AMR.

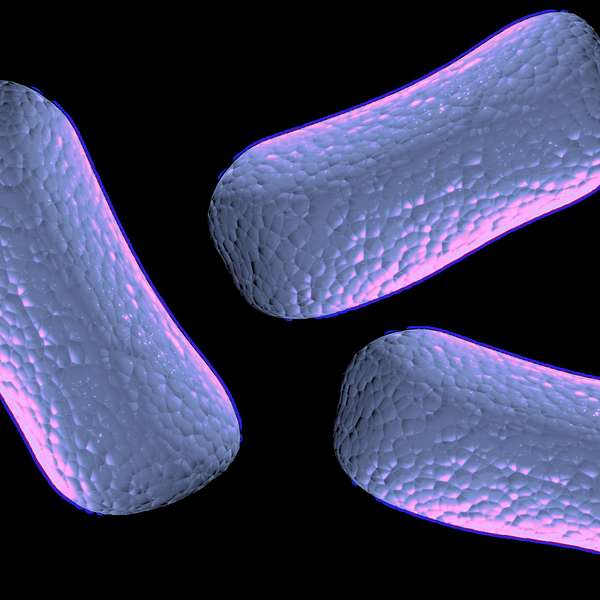

AMR occurs when bacteria develop resistance to antimicrobials, such as antibiotics, which makes it so that we can no longer use them to treat disease.

Brenda: Right. So in our last episode, we discussed phage therapy, an alternative way to eliminate bacteria by using viruses instead of antibiotics. This could be one of many ways to reduce AMR, especially in livestock farming.

Elliot: And for this episode, we’re looking deeper into the scale of the problem. We sat down with Arshnee Moodley, an ILRI scientist and an expert on AMR.

Brenda: As well as the science of AMR, we’re looking at why some people – especially those living in low- middle-income countries – get the worst impacts.

Elliot: Though I think it’s also important to remember that AMR isn’t just a danger to the Global South.

Arshnee: It's a global problem. And I think we accept that it is a global problem. And there is a general buy-in globally. The question is about how much resources have we invested in addressing this particular topic. And what we can see in high income countries, the investment has been enormous

If we have to look what has been the investment in low and middle income countries, we are far behind. So but it's not just a high income problem or a low income problem, it's everybody's problem.

Elliot: So, Dr. Moodley--who’s a microbiologist by training--started doing AMR research while she was still a graduate student.

Arshnee: It was, you can either do disinfectants, or you could try to figure out why this bacteria is resistant to these drugs.

Brenda: ‘Why this bacteria was resistant to these drugs’. That’s basically what AMR research is about.

Arshnee: So basically, if we start from the fact that we get sick by bacterial infections, or rather, micro organisms can cause infections in humans and animals and plants, and we need to treat those infections. And so we use anti microbials to treat them. But what happens over time, because these organisms are incredibly amazing, they develop resistance to these particular anti microbials. And that is essentially in a nutshell, what antimicrobial resistance is, is when the drugs virtually, they don't work anymore

Brenda: AMR isn’t new. It’s a problem that we have been facing for a long time. When Alexander Fleming, who discovered the world’s first bacteria killer, penicillin, accepted the Nobel prize in 1945, he warned that misusing antibiotics could create AMR.

Elliot: Right, and now we’re already seeing devastating consequences.

Brenda: Like we mentioned in the last episode, each year, 700,000 people die of AMR, and 90% of these deaths are in low-income countries in Africa and Asia.

Arshnee: In the 1960s, something came out. The Swann Report was launched. And basically, that report already then suggested that the use of antibiotics in agriculture was going to become a problem. And now we're just kind of seeing the fruits of those predictions basically

In specific pathogens, we do see you do find multi drug resistant strains, where you have very few, little to no options really for treatment. So I think we are already at that point in specific countries with specific pathogens

Elliot: And so, what happens if we don’t take action against AMR? What sort of scenarios should we expect to see 20 or 30 years down the line ?

It looks fairly grim. So the O’Neill Report projects that by 2050, some 10 million people would die annually as a result of an anti microbial infection. And the World Bank then tries to look at economically what will be the effect on GDP. And also globally economy, it's expected that AMR would have a significant effect on that by shrinking the economy, which will be devastating, right? We are more people, we will be continue to be more people. So how do we balance that

So right now, it's a lot of numbers, but the projections are fairly grim, if we don't do anything.

Brenda: Yeah. That’s extremely grim. So what can we do about this?

Arshnee: when we look at the sort of any action plan, there are five key areas that one has to address.

One is about raising knowledge amongst the different stakeholders, community, farmers, veterinarians, policy makers, everybody should be aware that this is a problem and how does it arise, and what can one do in order to mitigate that?

The other thing is surveillance. Surveillance is incredibly crucial. How do you know that your intervention is working if you don't have baseline data or any data to compare it to?

So I think that that, and also where should you make the intervention. We don't have an infinite amount of money. So we need to target it. And where should that target be, so that it's cost effective.

The other thing is about optimized treatment, both in the human side and in the animal side. An optimize treatment comes into play when we talk about diagnostics, making sure you're making, you know, you're making treatment decisions that are evidence based. You take a sample, you send it to the lab, and you know that it's an E. coli that's going to respond to this particular drug.

The other thing is about infection prevention and control. So if we can reduce the burden of infection either through you know good decontamination, good hygiene measures, we use vaccinations, these are all kinds of things that have to be going on almost simultaneously in order to be able to control AMR. what has been done is that a little bit of everything. We’re raising the awareness amongst the different stakeholders, we're trying to, you know, capture data on how much drugs are being used, why are they being used? And how much resistance is there? And how is resistance transferring through the different ecological compartments? Another thing is about how do we reduce the burden of infections? What do we need to do there?

So a little bit of everything is happening in different countries. Each country has a national action plan. So you know, almost all countries now do have a national strategy, on how to address antimicrobial resistance. So there is a plan, it's about executing the plan now, which is always the challenge.

Brenda: And the challenge is that countries already have different problems and priorities.

Arshnee: So I think if you had to ask a low and middle income country, what are their health priorities? They're likely to give you things like HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, respiratory infections, I mean, infectious diseases, right? If you had to ask a high income country, what are their health priorities, it's likely to be obesity, something related to that, very, very different priorities. And that's because the burden of infectious diseases is not the same in high income countries as in low income countries. And so, AMR then becomes another problem for low and middle income countries to address. And you can’t address AMR without having actually having good systems in place. And that was what, you know, allowed high income countries to implement a lot of the AMR, or AMU reducing interventions was because they already had the existing infrastructure, and then they built upon that. We don't have those same infrastructures. And so we can’t add another problem. AMR, I feel, is like another problem for low and middle income countries to address, and they simply don't have the resources to invest solely on this problem.

Brenda: It sounds like a problem of whether countries can afford to prioritize AMR. So what can these countries actually do to address it? Arshnee said something about a surveillance system earlier.

Elliot: Yeah, so that’s essentially a monitoring system that countries can use to collect data about potential AMR microbes, and share with each other.

In order to develop treatment guidelines, you have to know the burden of infection

so, until you have good surveillance data to show you what are the trends of resistance in key pathogens, it will be very difficult to come up with the treatment guidelines

Arshnee: So basically, countries do have a national action plan of which part of the National Action Plan is the need to conduct surveillance. That's them. But whether countries in the low and middle income context have that a functional system, I'd say no. It is incredibly expensive to have a yearly a monitoring system. I think for Kenya, it was estimated in just the human side, to be about $2 million to implement a surveillance program in human side. But ultimately what we want is not just human, we also want the same in animals. And we also want it in our food. And we want an integrated system. And I don't think countries have the resources to do that. So as it stands now, I would say there is no annual surveillance program

Elliot: And what about AMR and the livestock sector? There are specific challenges. Many people around the world—including farmers in the Global South—tend to overuse or misuse antibiotics in their livestock to prevent infection, to treat diseases, or even just to make their animals grow faster.

Brenda: Okay, so obvious question - why can’t we just restrict the amount of antibiotics that farmers can use on their livestock?

Arshnee: it's a combination of problems. One thing is that, particularly the users of the drug may not know how to use them correctly. Another thing is that may not have alternatives in order to improve their production system or their production practices. And therefore this is a very easy tool to use, rather than maybe investing in good biosecurity, routine vaccinations, good herd health, and things like that. This is just the easy way out. So it's much more easier to go down to your agrovet and buy a you know a dose of an antibiotic and give that to your animals, than understanding what is the root cause and been able to then invest in that. A lot of the farmers that we work with at ILRI are smallholder farmers, they are financially insecure and may not necessarily have the finances, the resources in order to implement a good foundation

Elliot: So like Arshnee outlined before in the action plan against AMR, we can raise awareness of what AMR is, about how to use antimicrobials properly, and survey what’s happening in farming. But there’s clearly an economic problem here. Many people simply can’t afford to farm differently without jeopardizing their livelihoods.

Arshnee: that's one of the things that we're talking a lot about. We're asking farmers to change their practice to a better production practice, ultimately, so you reduce the burden of infection on your farm. And at the same time, that will then lead to a reduction of antimicrobial use, and hopefully, then a reduction in the selection of resistance on your farm. But these farmers are sort of living on the razor's edge of, you know, financial insecurity. And so also it's an investment to start the production. And so they may not have the capital in order to invest in anything, and they don't know whether they will get the returns. Because maybe, you know, the price of the commodity is very low, and it's unlikely that they will be able to get it. So they're very conscious about how much is this new intervention that we're asking them to do, and whether it will be profitable for them in the greater scheme of things.

Brenda: The problem is bigger than just getting farmers to invest in healthier practices though.

Elliot: Right, consider the things in a country which can prevent infection in the first place, or treat it if it happens.

Arshnee: the challenge is that in low and middle income countries health care, access to health care is a major problem. And so if we are not able to address that, and also the foundations of you know, anything that in order to improve sanitation access to, you know, clean water, good food, you know, so we reduce the burden of infection.

If we don't address those bits there, you're going to have any microbial use, and you also select for resistance, very high level of resistance in these communities. So that is the public health crisis. It is not just the AMR it's the health care system as a whole

Arshnee: You can't take away the antibiotic if these individuals cannot access health care facilities.

Brenda: And that’s also why lower income countries are more affected by AMR.

Arshnee: So it really is a very fine balance. And I think we need to be very mindful of the fact that the policies or the interventions that were taken in high income countries, is simply not going to work here, because the context is different. So we really need to understand the context and come up with a context specific intervention.

Brenda: We need to remember that AMR is a One Health problem that requires a One Health approach because at the end of the day, we are all connected.

Arshnee: We use the same type of drugs in humans as well as in animals, as well as in crop production systems, in plant systems. And so the resistance that are developing individually in these different systems are the same. And because we are sharing and the resistant genes are mobile, you know, they're able to transfer from one organism to another. And we don't live in a little isolation, we live together with all the other sectors. And that's what makes it a One Health is that we use the same drugs, same resistances is occurring, and the resistance are being shared between the different sectors

Elliot: And resistance can reach the most surprising places.

Arshnee: there was a really nice paper that was published a few years ago looking at an isolated village in the Amazon. So a village that have not been treated, and they live in an isolated area, but yet they were able to find pathogenic bacteria carrying resistance of clinical importance. How did it get there? Well, in theory, we don't live in isolation. We share an environment, birds flying overhead, water, things like that. So why should somebody in Europe care about resistance here in Africa? Well, we live in a global system. Our food travels, I mean, in Europe, you can buy you know bananas from South America, and you know our food is also a mechanism in which they can carry antibiotic resistant organism. But at the same time, you have migrate, wild birds that are flying overhead and they have been shown to carry drug resistant organisms that are clinically relevant. So yeah, we also travel. I mean, we like tourism, we come here, we eat the food, we drink the water. So we are exposed and travel is actually one of the risk factors for bringing drug resistant organisms back home.

Elliot: So, where does all this leave us now? How do we move forward and address these problems, especially since, as we’ve mentioned, the problems associated with AMR look vastly different across the world?

Arshnee: I think that that is the challenge. And that is the discussion now, is one thing is that how do you make AMR a priority, a political priority? Because ultimately, what you need is investment within the area. And what should that investment be? And what is the cost benefit? And who should make that investment? I think these are all the sort of the questions that we need to be asking ourselves and be able to answer them

Brenda: Low and middle income countries are disproportionately affected due to things like a lack of infrastructure, surveillance, and money. With other problems at bay, investing in AMR is difficult. But Arshnee gives us the first few steps policymakers can take.

Elliot: And maybe a decent surveillance system would be a good starting point for many countries. Although the question still stands, where is that funding going to come from?

Brenda: And that’s definitely part of the challenge. What’s clear is that it’s not an insurmountable issue. There are clear opportunities to bridge those gaps, but those opportunities need to be taken sooner rather than later.

Elliot: And most importantly, this problem is not going to be solved in isolation because we are all connected. And that’s a great place to leave off for today! Thank you so much to Dr. Arshnee Moodley for taking the time to discuss AMR with us today.

Brenda: And thank you to our listeners for joining us. If you enjoyed today’s episode, we hope that you will leave us a review, and please don’t forget to subscribe!

Elliot: We’ll catch you next time on The Boma. My name is Elliot Carleton.

Brenda: And I’m Brenda Coromina